What would a city look like if it empowered seniors to be healthy, vibrant, and productive members of the community? That’s the question that city leaders in Long Beach, California, sought to answer with a new report analyzing gaps in resources and services for the city’s older residents.

In a city of 470,000 people, one quarter of residents are over the age of 50 and nine percent are over the age of 65. Nearly 30 percent of residents age 65 or older live alone, and 14 live below the poverty line, a number that is expected to grow to 22 percent by 2025.

The city’s Community Health Bureau (CHB) has been aggressive about responding to the growing need for programs and services for seniors. It created the Long Beach Healthy Aging Center, one of the first cities to designate an office entirely to senior services. Last fall, it enlisted FUSE fellow Karen Doolittle to continue to identify gaps in programming for the city’s aging population and develop more comprehensive approaches to meeting their needs. The process involved more than 60 stakeholder interviews, extensive secondary research, and in-depth statistical analysis. The results of the gap analysis were presented at a May event devoted to reimagining aging in the city of Long Beach.

A Holistic View

One of the insights that emerged from this process was the need to take a holistic view of health as it relates to seniors. “We need to see health as more than physical health,” said Tiffany Cantrell-Warren, CHB Manager for the City of Long Beach. “It’s not just about discharging seniors from the hospital.”

The analysis underscored the need for more services that go beyond clinical care, especially in-home support to assist seniors with daily chores, like picking up medicines or buying groceries. This is particularly important in the face of the growing prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia.

An expansive view of senior health also takes into account the needs of Long Beach’s distinct senior populations. Gary Cucchiaro, 78, a longtime resident of Long Beach and a volunteer at the Long Beach Senior Center says he would like to see housing support included in the city’s plans to assist local seniors, who are among the most impacted by high housing and rental costs.

“Every day, five or six people come in looking for housing,” said Cucciaro.

Long Beach also has a large community of Cambodian refugees, some of whom may require more intensive support, such as language assistance or trauma-informed care. “You don’t know what someone has been through when they come through the door,” said Cantrell-Warren.

Over the next year, the city will be looking at these various needs in further depth, developing strategies to support a more holistic view of senior health.

A Focus on Intergenerational Equity

Core to CHB’s mission is ensuring that Long Beach is as welcoming for older adults as it is for everyone else, for both big and small day-to-day experiences. For example, CHB staff members have gone on “audit walks” with seniors to observe the mobility challenges that seniors encounter while moving through the city. “We learned where there were cracks in the sidewalks and which roads seniors don’t cross because the walk time is too short.” The city is also applying universal design concepts to make sure that city spaces, such as libraries and parks, are accessible to seniors.

Wherever possible, the city is working to incorporate programming for seniors into existing resources. “Instead of having a separate senior plan for mobility or parks, we want to incorporate programming for seniors into existing plans.” As just one example, the city is in the process of revising its economic development plan to include the policy needs of seniors, who launch new businesses at nearly twice the rate of people in their twenties. “It’s about taking all of these available resources and services and seeing where we can add in a layer of intergenerational equity,” said Doolittle.

The city is looking for creative ways to leverage the unique contributions of seniors as mentors, volunteers and caregivers to children and youth. Barbara Howard, a 72-year old volunteer at the Long Beach Senior Center, believes that educators can partner with the center to incorporate cultural programming into schools. “I’ve learned so much from coming here and meeting people from all over the world. I’ve met Russians, Germans, Filipinos, Cambodians, Egyptians,” Howard said. “Kids can learn from them.”

That learning goes both ways, said Cucchiaro, who sees technology as a particularly promising area for young people to engage seniors. “We have some seniors who don’t even know what a computer looks like,” he said. “Having young people around to assist can be very helpful.”

This kind of intergenerational transfer of knowledge can have a powerful, positive impact on the community, while also helping to address one of the most significant threats to the wellbeing of seniors, especially those who live alone. “Intergenerational equity is a way of getting seniors out of isolation,” said Doolittle.

“There’s a lady who calls just to ask me ‘What time is it?’,” said Howard. “Some people just want a little conversation.”

Enhancing Coordination Among Service Providers

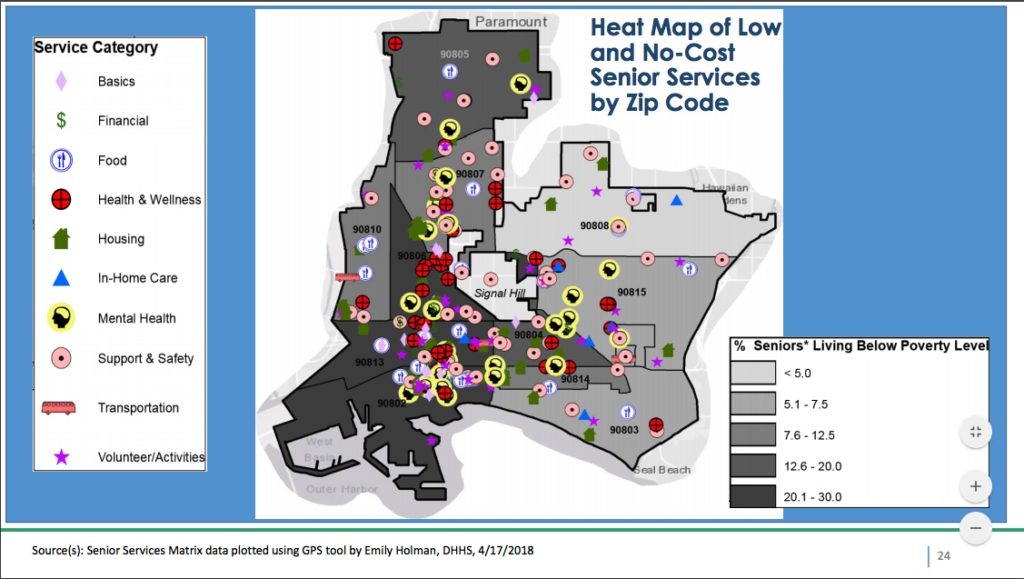

To better understand the landscape of available resources, Doolittle produced a series of heat maps showing where service providers were located throughout the city. She then cross-referenced this data with the senior population by zip code and income level to identify gaps. “The next step is to figure out how to better coordinate and integrate services so we can reduce costs and get even better outcomes,” said Doolittle.

One of the biggest challenges is closing the loop on referrals, and making sure that seniors are actually receiving the services they need. “How do we put a mesh around the system so we’re making sure that the client we referred is making it to that referral?” Cantrell-Warren said.

Adding to the complexity is a need to manage what kind of information can be shared among service providers without violating patient privacy regulations. These kinds of structural challenges require broad support from city leaders. “The gap analysis helped demonstrate to city officials the specific needs,” Cantrell-Warren said. “And it showed how much support there is within the community for these changes.”

Picture a city that empowers seniors to be healthy, vibrant, and productive members of the community. If CHB is successful in implementing its proposed reforms, it could look a lot like Long Beach.

Rikha Sharma Rani is a Bay-area based writer and journalist. She is the founder and principal writer at Rickshaw Writers. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, USA Today, Politico Magazine, The Atlantic, HuffPost, Oakland Magazine, and more.

[Photo credit: Hermes Rivera]