Los Angeles County is home to the largest jail system in the nation. On any given day, around 20,000 people are housed in one of the county’s jail facilities. For many of them, jail was the inevitable result of untreated mental or physical illness, substance abuse or drug addiction.

A joint report by the Treatment Advocacy Center and the National Sheriffs’ Association called the county’s jail system “de facto the largest ‘mental institution’ in the state … usually in the running for the dubious honor of being the largest psychiatric institution in the nation.”

FUSE fellow Tom Pyun is working with the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services to create an inmate processing system that better accounts for the medical and mental health needs of people in jail. Drawing from best practices across the country, Pyun is implementing recommendations for how to more reliably and efficiently assess health needs, avail of community-based health resources, and optimize data collection and measurement.

“When clinical staff work with this population, they become our patients,” said Ghaly. “That’s how we treat it.”

Pyun’s work follows a major reorganization of how healthcare is managed within the county jail system. Previously, oversight of medical and mental health care was divided between the Sheriff’s Department and the Department of Mental Health. This year marked the final phase of a transition in which the provision of all health services will be managed by the Department of Health Services (DHS) and overseen by a medical professional.

“The driver was to have one integrated health system for jails,” said Dr. Mark Ghaly, Director of DHS Community Health and Integrated Programs unit. “The idea was that, if a single department was responsible for patients, we would deliver better care and do it more efficiently.”

Patients First

The reorganization is part of a broader effort to reframe how people in need of healthcare are perceived while behind bars. “We have to keep reminding our staff that they’re our patients,” said Jackie Clark-Weissman, Director of Correctional Health Services for DHS. “We put that at the forefront because, working in these jails, it’s easy to take on the mindset of custody staff. I make it an emphasis that we refer to our patients as patients.”

But there are tensions. Law enforcement officials have a mandate to protect public safety and see that as their primary responsibility. The different lenses through which members of the jail population are viewed—either as inmates or patients—adds to the complexity of the challenge.

“There’s an internal perspective that keeping everyone separated and isolated is more safe.” said Pyun. “But healthcare providers believe that to provide quality care you have to examine patients, you have to talk to patients, you need private spaces—all the things that we take for granted as people who aren’t part of the correctional system.”

Part of Pyun’s challenge is to facilitate the shift to a patient-centered approach, while also addressing the public safety concerns of law enforcement officials, whose buy-in is essential if changes to the system are to be effectively implemented.

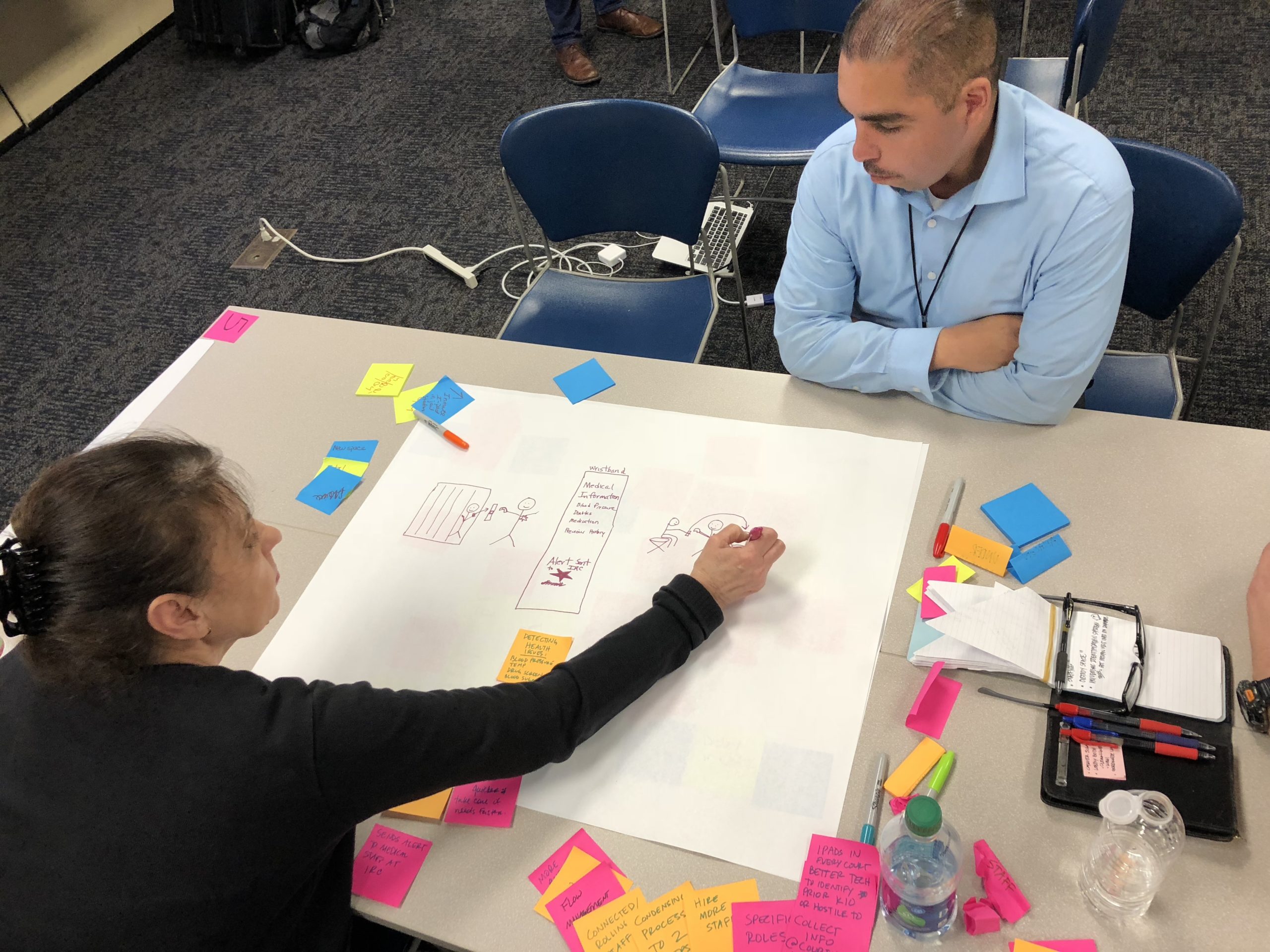

Pyun recently brought together many of the stakeholders involved for a facilitated conversation about redesigning the process by which inmates are arrested and directed through different facilities. At the table were leaders from the Sheriff’s Department, DHS, and two people with lived-experience inside the system.

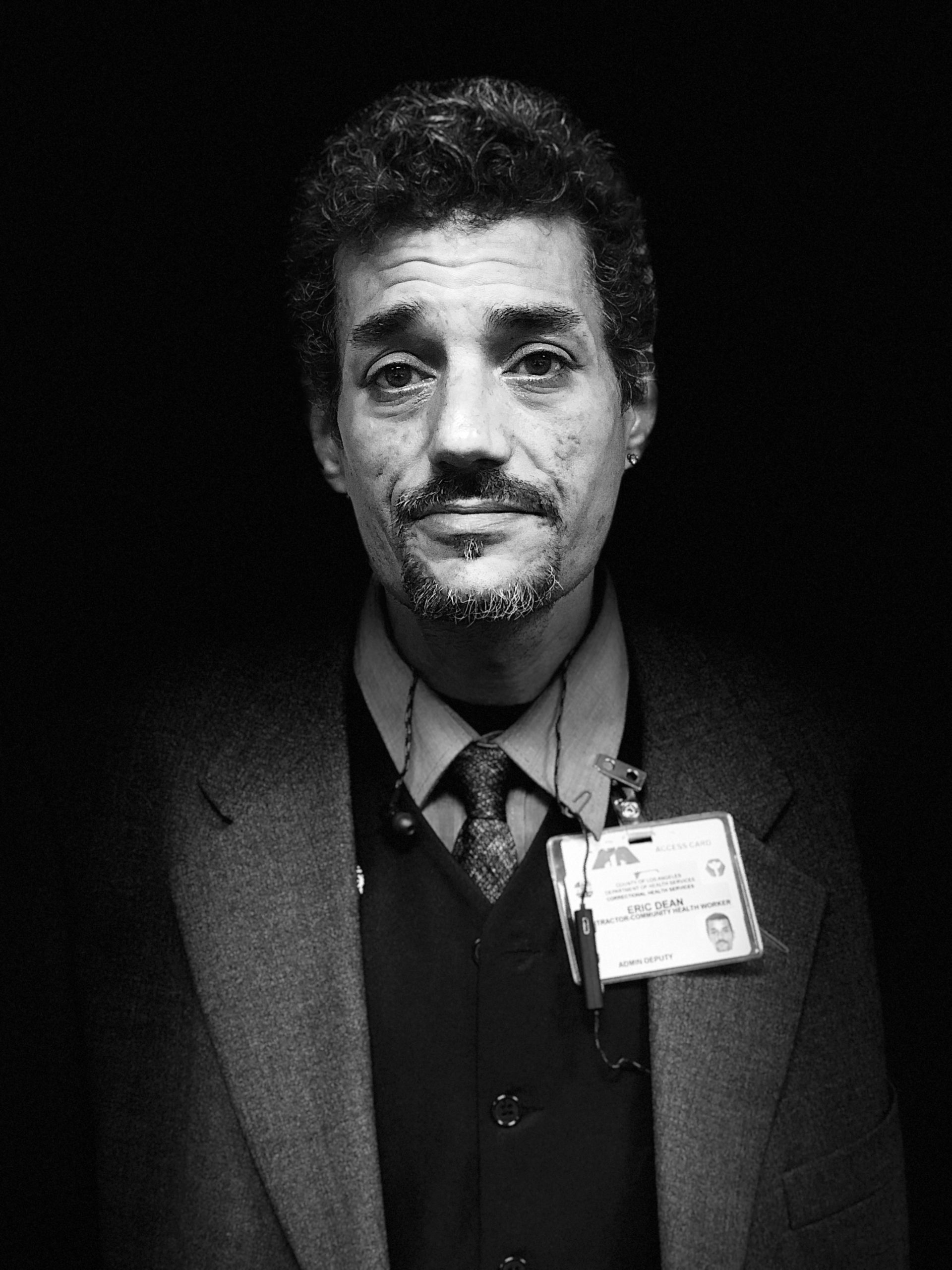

Eric Dean and Marcelo Perez are community health workers for L.A. County Health Services. Both have spent time in jail and now help individuals who have been released from the system reintegrate into civilian life.

“The correctional staff needs to remember that there are other issues besides safety, and [medical staff] needs to remember that there are other issues besides efficiency of operations,” Dean said. “It’s hard to blend the two, but both sides need to realize that we are dealing with people. Inmates all have names and birthdays and more to them than their incarceration.”

Perez believes law enforcement has come a long way. “Back in 2000, the deputies were more aggressive. When I went back in 2010, there was less of that. There was more of a communication. They’re not just barking orders, they’re communicating with people now,” he said. “I know the sheriff’s department was making a big effort to respect inmates and try to defeat that culture of antagonism and arrogance that unfortunately sometimes comes along with power and authority. I think they have done a good job of it.”

Tailoring To Different Needs

The first point of contact for individuals entering the L.A. County jail system is the Inmate Reception Center (IRC). Every day, the IRC processes an average of 400 people. Most of them require some form of medical care, anything from treatment for serious mental illness or drug abuse or withdrawal to prescriptions for chronic disease like diabetes and heart disease. Many of them will wait for up to 48 hours and undergo multiple evaluations before seeing the doctor on staff, a system that creates an enormous backlog of patients in need of care.

“Patients are getting denied care,” said Clark-Weissman. “An inmate enters the facility and there’s a 15-question questionnaire asking patients about medical and mental issues. Sometimes they divulge their condition and sometimes they don’t, partly because questions are being asked by custody assistants. If they say ‘yes’ to the questions, they’re referred to medical, where they fill out more messy questionnaires.”

Pyun is working with county officials to create a more streamlined, less redundant process that improves the quality and efficiency of care. Their approach is inspired by a crucial insight: that different patients have different needs, and their needs can be addressed in different ways.

Instead of funneling all inmates through one channel, a new system is being conceived in very early stages of discussion, which would segment the population based on medical need. In this scenario, healthy men would be referred directly to housing. Severely ill patients would be taken to an urgent care facility currently in development. Patients detoxing from alcohol, and soon opioids and tranquilizers, would be sent to a detox clinic. Those in need of immediate psychiatric treatment would receive expedited mental health services, and non-urgent psychiatric and medical patients would be evaluated and placed accordingly. “By putting people in the different spaces, you’re going to improve the flow,” said Pyun.

Other ideas that would release the backlog of inmates: a revised shuttle schedule that brings inmates from courthouses throughout the day, rather than only in the evenings; conducting health screenings and classifying inmates at sheriff substations or county courthouses rather than at the IRC; leveraging technology for onsite healthcare providers to streamline patient data efficiently.

While there is still a lot of work to be done, the momentum for change in L.A. County is strong, and it’s being driven by a fundamental shift in how the county views its role–and how it views people who too often cycle in and out of the system because of underlying illness or disease.

“When clinical staff work with this population, they become our patients,” Ghaly said. “That’s how we treat it.”

[Photo credit: Pexels]