Last August, New Orleans weathered one of the worst flooding events since Hurricane Katrina, a record-breaking rain that tested the city’s pumping and drainage system. Within a year, New Orleans has made huge strides toward rebuilding its civic infrastructure with the help of Sewerage & Water Board of New Orleans (SWBNO) and other city agencies.

Despite this significant progress, New Orleans, which sits below sea level, must be on constant guard against the long-term effects of sea-level rise and related climate-change effects. As part of this effort, FUSE executive fellow Priya Dey-Sarkar worked with SWBNO to stabilize the drinking water and drainage infrastructure, identify large-scale power generation alternatives, and improve industrial and process safety. (SWBNO is one of the largest consumers and generators of energy because of the energy it takes to run the stations.)

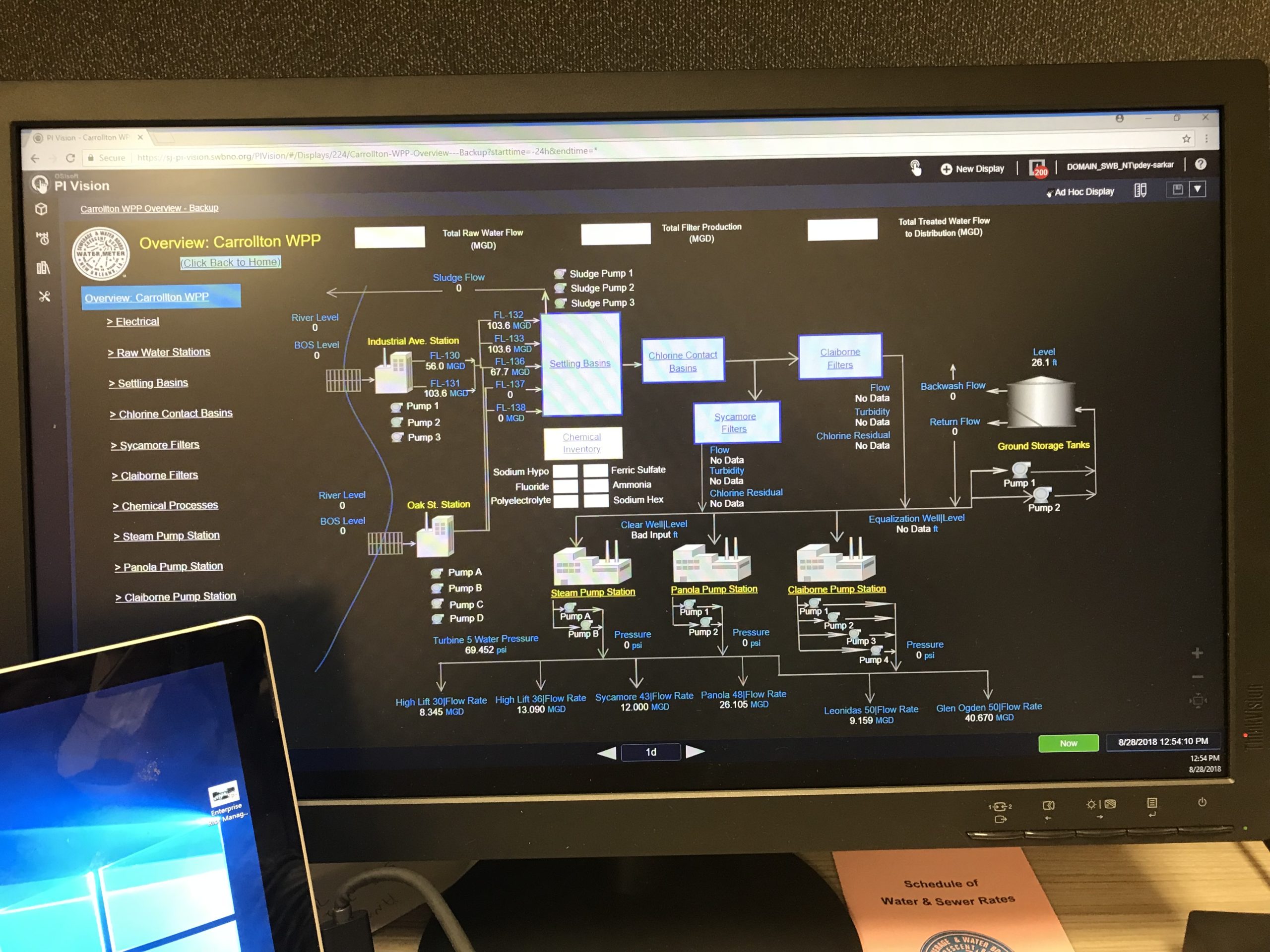

In that time, the new data management system she helped roll out gives city officials a real-time, birds-eye view of municipal drinking water and drainage facilities. Dey-Sarkar has also supported the agency through multiple boil-water advisories — government-issued directives to consumers when drinking water may be contaminated — and four major rain events that threatened the city with flooding, helping the agency monitor flooding and communicate critical data.

Contending with these and other challenges has yielded some important insights about how cities can rebuild after an infrastructure crisis. We asked her to share some of the lessons she’s gleaned.

1. Set priorities and focus on them relentlessly.

Managing a crisis involves tackling many urgent problems at once with the involvement of multiple, overlapping agencies, so it’s important to establish priorities upfront and continuously reinforce them. In New Orleans, three unwavering priorities — addressing power and pumping failures, ensuring the reliability of power turbines, and resolving staffing shortages — guided the city’s long-term recovery efforts, helping to align stakeholders and direct resources. Nearly every meeting centered around these priorities, in part because a handful of city leaders continuously sought updates about their status. In 10 months the city was able to address several years’ worth of unfunded maintenance. There has not been a significant flooding event despite multiple heavy rain events since last summer, due to this effort and focus.

2. Work with what you have.

One of the most resilient turbines in New Orleans today was built in the late 1800s. The museum-worthy turbines from more than a century ago are still capable of powering the drainage operations of nearly 50,000 cubic feet per second of water across multiple drainage basins. Not only is it prohibitively expensive to purchase a new set of turbines, the assumption that old equipment is inherently less resilient than newer, shinier models doesn’t always hold. What often matters is how skillfully equipment is used and how regularly it is maintained. The drainage system in New Orleans, for example, needs constant maintenance and updating. Complicating matters further, the agency must carefully time maintenance calls so that equipment isn’t out of commission in the event of, say, a massive rainstorm. Rather than outdated equipment, often the problem is lack of resources (money and staff) and competing priorities (operation versus maintenance). Rather than spending money on new equipment, finding solutions to addressing resources and establishing priorities has been New Orleans’ key to drainage system stabilization.

3. Leverage existing talent.

In the immediate aftermath of a crisis, government agencies at times bring in outside contractors to support or even spearhead recovery efforts. In some cases, these outside contractors have little to no connection to the people or places affected. Internal staff, in contrast, are usually part of the community and must personally contend with the consequences of infrastructure breakdowns. That connection to those affected by the crisis can be a powerful force in recovery efforts. What’s more, when problems or questions arise, frontline staff are often the best equipped to answer them. Before engaging contractors or escalating issues to staff higher up in the organizational hierarchy, doing a robust review of current staff in those roles, and taking stock of the institutional knowledge can help determine the right approach. Most of the staff have years, if not decades of on-the-job experience working in that agency and can clearly articulate the city’s needs.

4. Communicate challenges as openly as possible—including to the media.

During times of crisis, knowing how to convey the right message internally and with media is critical. It’s that much more important when it comes to relaying technical and infrastructural data, which can be confusing to the layperson. That’s why it’s important to communicate clearly and consistently with the public and to media the myriad intersecting issues around large-scale infrastructure challenges. What’s more, acknowledging and celebrating the contributions of staff internally and externally, especially in times of crisis, can go a long way toward sustaining progress and morale.

5. Acknowledge that sometimes infrastructure has its operating limitations.

If it rains more than an inch in an hour in New Orleans, there is likely to be flooding — even if pumps are working at 100 percent capacity. Infrastructure, no matter how sophisticated or well-functioning, does not have the ability to protect against every eventuality, especially in a city surrounded by water. That’s why New Orleans is working to better prepare for the next infrastructure crisis, and seeking new solutions to their challenges.

Like most cities, New Orleans is dealing with complex challenges with limited resources. The lessons they’ve learned about resilience and creative problem-solving can be beneficial to other cities facing similar challenges.

Rikha Sharma Rani is a Bay-area based writer and journalist. She is the founder and principal writer at Rickshaw Writers. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, USA Today, Politico Magazine, The Atlantic, HuffPost, Oakland Magazine, and more.

[Photos credit: Priya Dey-Sarkar]