Seeking Diverse Voices

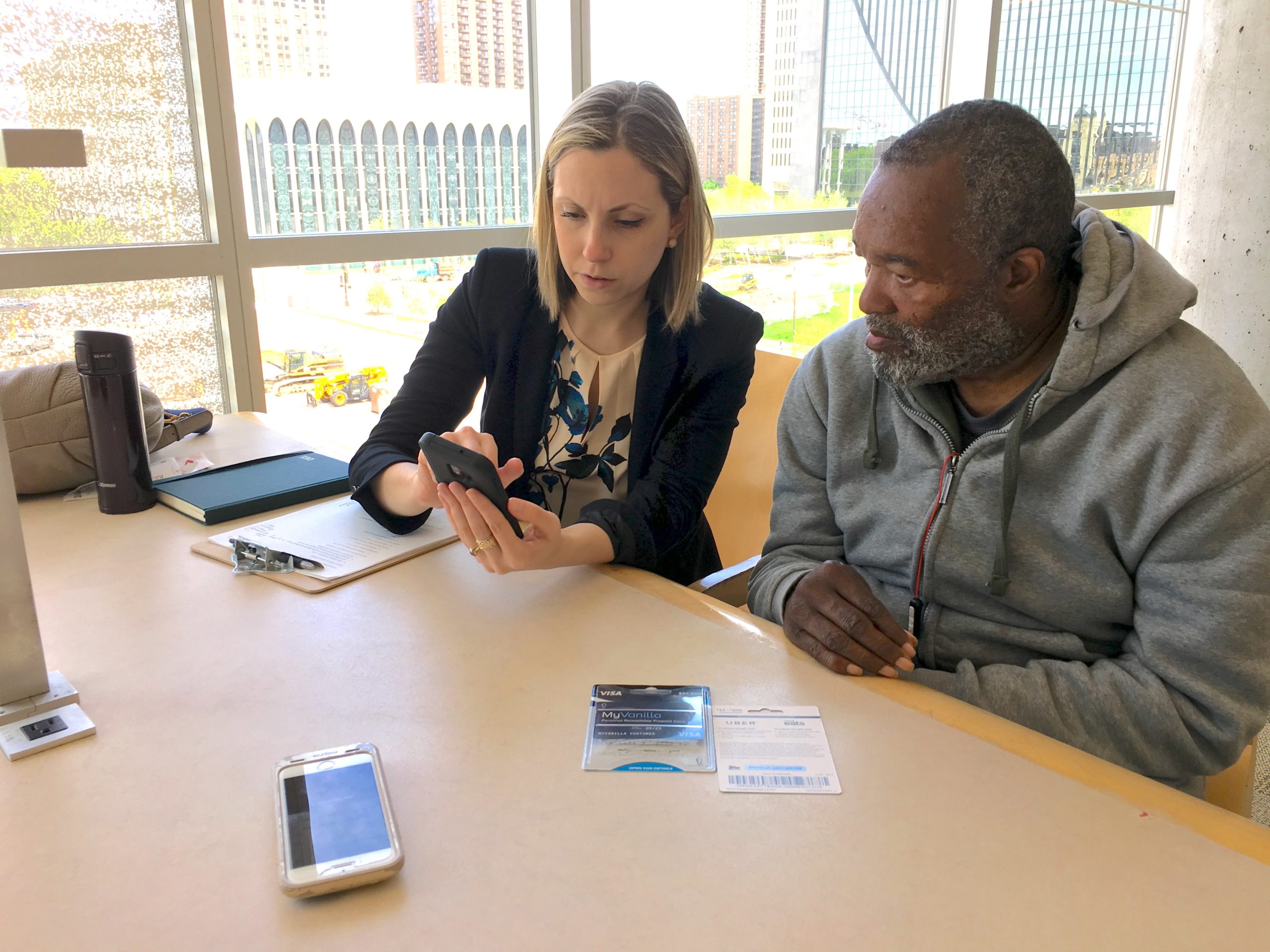

To hear directly from residents, businesses, and community organizations, Minneapolis hosted eight community workshops. For a diverse range of perspectives, the city connected with communities of different cultures, languages, and abilities, hosting small group discussions on transportation topics. The Department of Public Works collaborated with the city’s Neighborhood and Community Relations Department and partner agencies to identify key audiences and to prioritize engagement with groups that have been historically underrepresented in transportation decision-making processes, specifically communities of color, including the city’s large East Asian, Somali, and indigenous populations. The city also issued a call to community-based organizations, individuals, and artists for engagement services designed to broaden community input.Before you think about technology and innovation, you need to know and understand what your communities’ priorities are and what you value. Then you can create the policies, the systems, the infrastructure, the ordinances — whatever is needed — to get the outcomes your community wants. — Danielle Elkins, Minneapolis FUSE fellowAt one community workshop, Elkins and her colleague Alexander Kado met Vernon Smith, a man who had become homeless after the factory he worked at was moved to a suburb of Minneapolis and he could no longer get there. To better understand his transportation challenges, the pair spent a day with Smith (see sidebar, “A Day in the Life”), which led to some important insights. “Everything came back to one single thing,” Elkins said. “If you don’t have a credit card or a bank account, everything is a million times harder.” According to an FDIC report, 1.5 percent of households in the Minneapolis-St. Paul Metropolitan area were “unbanked” — did not have an account with a bank or similar financial institution — in 2017. After spending a day with Smith, Elkins and Kado realized that financial inclusion must also be addressed when considering transportation challenges. One solution already being implemented: The city’s bike share provider Nice Ride is partnering with the nonprofit Prepare + Prosper to provide a low-income rate and the ability to access bikes to those who are unbanked.