“The Patient Journeys was like having another voice at the table that spoke to the importance of the patient experience.” — Amy Peterson, care experience managerWith such an expansive network and a growing number of patients, maintaining a positive, consistent customer experience across SFHN facilities has been a challenge. During the past several years, SFHN has trained employees on the principles of service excellence and relationship-centered communications, and it has implemented patient-satisfaction surveys. But SFHN knew it needed to do more. To craft and implement an approach to patient-centered service, organization leaders assembled a Care Experience Advisory Council (CEAC) with representatives from across SFHN. Leaders also partnered with FUSE executive fellow Cori Schauer, who helped structure the CEAC for optimal functionality. Additionally, Schauer worked to determine the strengths and weaknesses of the SFHN system in order to recommend ways to improve.

Framing the Problems

To comprehend this vast and diverse ecosystem, Schauer employed a human-centered design approach, which looks at issues from the perspective of the people involved and devises solutions based on their concerns. This approach helped her identify needs, frame problems, and explore potential solutions for both patients and staff. Schauer began by observing and interviewing patient-experience teams at SFHN’s two hospitals and various primary- and specialty-care facilities. From these interviews, two important insights emerged that shaped her approach to the rest of the fellowship. First, the way feedback is collected across SFHN is siloed and not uniform, so no one was able to see the big picture of how SFHN did — or did not — meet patient needs. This also meant that SFHN staff didn’t know the experience of a patient traveling through the network, especially from one department to another, such as from primary to specialty care. Second, each facility had a unique culture, which resulted in varying priorities for the patient experience across the network. The patient population and priorities in a long-term stay facility, for instance, were different than an emergency room setting. Schauer was able to identify the strengths unique to each of the care teams, but she also noted that differences in cultures sometimes resulted in silos and conflicts among various parts of the network. Armed with this knowledge, Schauer wanted to understand specific needs, so she conducted ethnographic research, interviewing patients and staff and performing 29 hours of in-clinic observations and job shadowing. As it turned out, interviewing patients was no easy task; privacy laws did not allow access to patient files or health records, and many patients’ contact information was not accurate. However, she eventually obtained a list of 30 people to contact. Schauer found that patients tended to have chronic health problems, which in some cases were compounded by mental-health or substance-abuse issues. Moreover, patients with chronic health problems had an especially hard time understanding how and when to access different doctors across the network. These patients also related that the handoff from primary to specialty care left them feeling as if they were starting the care process all over again, with new doctors asking the same questions for another set of paperwork. The more difficult the process, the less satisfied and, ultimately, more distrustful of the system patients became. Patient experiences were also influenced by their understanding of health issues, their cultural beliefs, and a variety of socio-economic factors, including income, place of residence, and education. From staff, Schauer learned that they had a difficult time providing feedback to one another, especially if they crossed departments or roles. For example, a medical assistant didn’t feel comfortable providing feedback to doctors about how they handled patient interactions, because, “They are doctors, and I’m not.” Similarly, doctors didn’t feel like they could provide direct feedback to team members, because the doctors didn’t want to break union rules by going around a manager. Staff also discussed what they call “burnout.” Although exposed to trauma on a daily basis, staff was doing little to deal with the personal effects of that trauma. The result was what they referred to as quick burnout, which led to shorter tempers and, in some cases, negative interactions with patients.The Approach

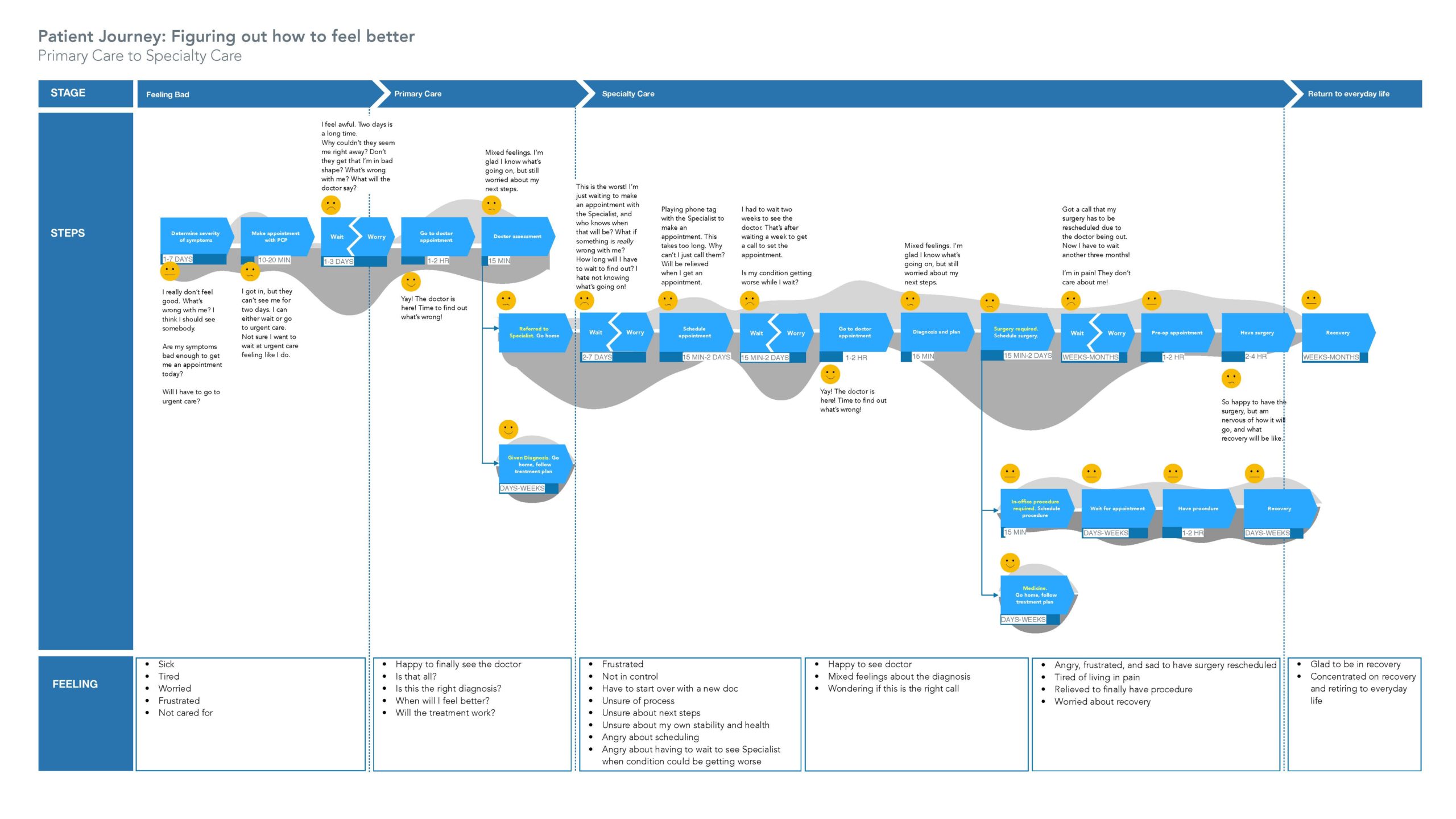

Equipped with these findings, Schauer determined that her focus should be on helping SFHN improve patient transitions, during which disparate cultures and processes would often increase stressors for patients. Furthermore, she provided SFHN staff with insights from her patient interviews to help them understand the patient experience. As such, Schauer devised the following priorities and recommendations. Use visualization to see the big picture: Schauer created a patient journey map, which provided a visual outline of the steps and emotions that patients experience when seeking care. The map was the first time SFHN had seen what it was like for a patient to travel throughout the network and transition between doctors and departments. It was eye-opening. SFHN was able to see the emotional highs and lows of the process and where it wasn’t meeting the needs of its patients. In one example, patients who had waited months for surgery were given two weeks’ notice that their procedures would have to be moved, delaying the surgeries for several additional months and resulting in great stress. “The Patient Journeys was like having another voice at the table that spoke to the importance of the patient experience,” said Amy Peterson, care experience manager in primary care. “Cori introduced a new vocabulary and new way of presenting information. The visualizations and patient-experience map felt very evidence-based and offered a practical perspective on improving a specific workflow.” Additionally, Schauer’s direct interaction with patients helped many of them work through issues, feel more hopeful, and realize the agency is on their side. Co-design solutions: Schauer held a series of participatory design workshops with primary care staff, giving them the tools to develop patient advisory councils and incorporate regular patient feedback into their workflow. At one of the hospitals, Schauer leveraged an existing patient council to hold ideation workshops. But instead of following the council’s typical format, which was to raise patient complaints, she encouraged patients to identify opportunities for improving their stay. Many of the suggestions, such as recognizing significant holidays (Dia de los Muertos, for example) and allowing patients to adjust the water temperature in their rooms, required only minor adjustments on the part of the staff. But they provided outsized impact on the patient experience, contributing to their sense of dignity and happiness. Schauer also provided guidance on standard practices for soliciting feedback, such as required consent forms, compensation, or other incentives for patient participation.