Bring the Community in Early

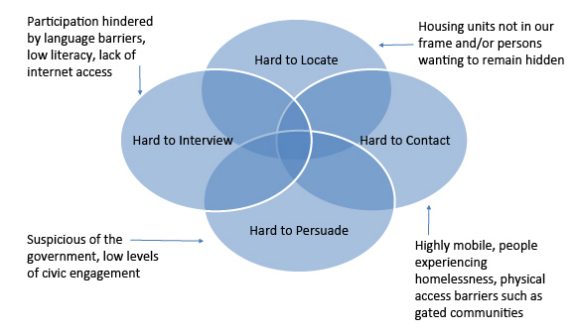

For many urban areas like Long Beach, the census process begins two years before those forms are distributed, when the Local Update of Census Addresses (LUCA) is conducted to confirm residential addresses. These are then shared with the Census Bureau, which uses the addresses to contact residents. “The tricky part is that there are people who live in garages, or in their cars in parking lots, or in other types of unconventional housing,” Afeworki said. People experiencing homelessness are one of the harder-to-count groups that the census can miss. Another is renters, who sometimes think — mistakenly — that the building’s owner is the only one who should be counted. Also included are children under age 5, low-income residents, people who don’t speak English, and people with disabilities. Additionally, residents with noncitizen status, such as immigrants and undocumented people, are often undercounted. Long Beach has a population of roughly 475,000 and is part of Los Angeles County, considered the hardest-to-count county in the U.S. Long Beach has the second highest population of hard-to-count residents in the County (5.9 percent), with the City of Los Angeles ranking first (50.59 percent), Afeworki explains. To help identify as many people as possible for the LUCA process, Long Beach hired community organizations familiar with neighborhoods and their residents.

The Challenges of Going Digital

Perhaps the biggest change to the upcoming census is that it will be largely conducted online, a move motivated in part by federal budget restrictions. For Long Beach residents who don’t speak English, providing a form in their native language should be more easily facilitated with the digital format, notes Afeworki. However, the challenge becomes reaching people without digital access, whether that is no computer or smart phone, or a limited data plan or no home wifi. In response, Los Angeles County and Long Beach are working to establish Census Action Kiosks around the city that residents can use to fill out census questionnaires. Most kiosks will use existing computers located at public facilities such as libraries, job centers, and community organizations.