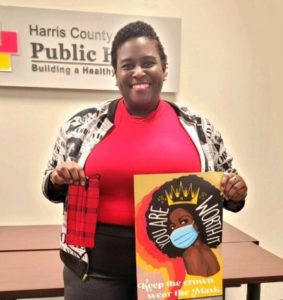

In summer 2021, when FUSE Executive Fellow Jometra Hawkins began working with the Harris County Public Health Department, the county was at the highest COVID-19 threat level.

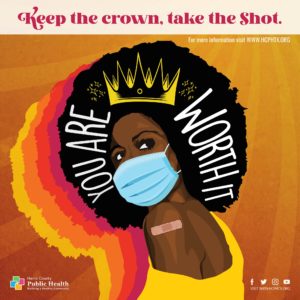

Despite the implementation of mass vaccination sites and drive-thru clinics, the rate of fully-vaccinated adults in the state still ranked 36th out of 50. Between vaccine hesitancy, access issues, and limited local availability, reaching a herd immunity goal of 70% seemed unlikely. “Being able to connect resources in the right places at the right time has always been something that I pride myself on,” Hawkins said. Having partnered with faith-based organizations on public health initiatives before, she asked, “How do we put all of these great organizations together and share resources?” She saw an opportunity in the recently funded partner vaccine incentive program. The largest county in Texas and the third-largest in the United States, Harris County required an organized, strategic COVID response. Staci Lofton, a Senior Policy Planner in Health Equity with Harris County Public Health explains, “The emergencies we usually deal with are focused in one geographic area or disproportionately impact one particular area, but COVID had no geographic limitations. We started, in June of 2020, providing services within the community. But the breadth of COVID-19 really pushed us to do more. We knew that social resources and social services were vital.” Hawkins and her equity team colleagues began by compiling data, creating a priority list of the top 25 zip codes, and then comparing the areas with positive COVID test rates and SVI (social vulnerability index) data. After identifying and targeting high-need areas, they found partners able to draw upon their community connections and trust to encourage vulnerable populations to get vaccinated. Local faith leaders were instrumental in the push to increase vaccination and testing uptake in at-risk Harris County areas.

Senior Pastor of New Bethlehem Baptist Church in Houston David L. Smith, describes how he became a community partner, “Initially in 2021, they reached out to me and asked if we would be interested in doing vaccines in the church, which was perfect—because it made it better for folks to just come to the church and get their vaccines, with no appointment. Plus, we’re in partnership with Berry Elementary School and Sam Houston High School. So, we were able to reach out to the wraparound specialists and let them know that there were some vaccines that will be available.” Pastor Smith also explained how he was also able to distribute antigen tests provided by the County to smaller churches in the area.

Hawkins and her equity team colleagues began by compiling data, creating a priority list of the top 25 zip codes, and then comparing the areas with positive COVID test rates and SVI (social vulnerability index) data. After identifying and targeting high-need areas, they found partners able to draw upon their community connections and trust to encourage vulnerable populations to get vaccinated. Local faith leaders were instrumental in the push to increase vaccination and testing uptake in at-risk Harris County areas.

Senior Pastor of New Bethlehem Baptist Church in Houston David L. Smith, describes how he became a community partner, “Initially in 2021, they reached out to me and asked if we would be interested in doing vaccines in the church, which was perfect—because it made it better for folks to just come to the church and get their vaccines, with no appointment. Plus, we’re in partnership with Berry Elementary School and Sam Houston High School. So, we were able to reach out to the wraparound specialists and let them know that there were some vaccines that will be available.” Pastor Smith also explained how he was also able to distribute antigen tests provided by the County to smaller churches in the area.

“A lot of these organizations we worked with are super underfunded, but they are also the ones getting the work done,” said Hawkins, adding, “We knew that they would benefit from the partnership.”The pilot program awarded a stipend to 10 churches for registering and getting 100 or more people vaccinated in the community. Harris County launched a simultaneous incentive program in August 2021, offering a $100 gift card to residents receiving their first vaccination. For those whose vaccine hesitancy was financially motivated, the gift cards provided a cushion to offset missed shifts or transportation costs. The initial pilot resulted in over 4,300 vaccinations, mostly of people who likely would not have been vaccinated otherwise. Recalling his experience working with Hawkins, Pastor Smith beams, “Jometra has done a good job. I think she’s a great leader, and she’s done her homework—she really understands this community. I worked with her with another organization a long time ago, and she just has a passion for community.”

Meanwhile, in Travis County—the fifth most populous county in Texas and home to the capital, Austin— FUSE Executive Fellow Jody McIntosh arrived to similar circumstances.

By the summer of 2021, only 30% of Travis County residents over the age of 16 had received at least one shot, and more than half a million people in the county remained particularly vulnerable to serious infection with a high risk of mortality. Like her colleague Hawkins, McIntosh recognized the opportunity to bring in an incentive program to increase vaccination rates in underserved Travis County populations.

Working with Travis County Health and Human Services and drawing off her nonprofit public health background, McIntosh seized the chance to partner with local organizations that could benefit from Travis County resources. “What we’re doing is amplifying the work they’re already doing,” said McIntosh, “While having them build trust in us, and hopefully building trust with the community at large.” Travis County Commissioner Jeff Travillion agrees that the trust-building aspect of this work is critical.

For McIntosh, the relationship and trust-building process begins with removing barriers.

For example, offering simple one-page forms, rather than complex grant applications. In collaborative partnerships, maintaining the relationship also means showing up consistently. “How do we continue these partnerships even after we’re over the hurdle of COVID,” asked Hawkins. “We want to share resources…interact with our community partners more, not just when we need them to do something,” she added. By acting as visible County partners, the fellows both hope to create transformative rather than transactional relationships with local organizations.

By the summer of 2021, only 30% of Travis County residents over the age of 16 had received at least one shot, and more than half a million people in the county remained particularly vulnerable to serious infection with a high risk of mortality. Like her colleague Hawkins, McIntosh recognized the opportunity to bring in an incentive program to increase vaccination rates in underserved Travis County populations.

Working with Travis County Health and Human Services and drawing off her nonprofit public health background, McIntosh seized the chance to partner with local organizations that could benefit from Travis County resources. “What we’re doing is amplifying the work they’re already doing,” said McIntosh, “While having them build trust in us, and hopefully building trust with the community at large.” Travis County Commissioner Jeff Travillion agrees that the trust-building aspect of this work is critical.

For McIntosh, the relationship and trust-building process begins with removing barriers.

For example, offering simple one-page forms, rather than complex grant applications. In collaborative partnerships, maintaining the relationship also means showing up consistently. “How do we continue these partnerships even after we’re over the hurdle of COVID,” asked Hawkins. “We want to share resources…interact with our community partners more, not just when we need them to do something,” she added. By acting as visible County partners, the fellows both hope to create transformative rather than transactional relationships with local organizations.

“A lot of people do not have a lot of contact with government,” said Travis County Commissioner Jeff Travillion, “Whenever the government comes up with a program, some are suspicious. If you work through local churches…fraternities and sororities…local teaching institutions, then we find that it is easier to reach communities.”

Leveraging government resources to support and invest in the community and faith-based groups makes sense from an efficiency standpoint.

Partnering with organizations that already have a broad reach and high levels of community trust builds trust by association. “You know, there are people who show up every now and then,” McIntosh explained. “They might look in, and the next time they might grab a brochure, then the next time, they might ask a question. And that fourth time is when they say, ‘Okay, I’m going to do this.’ So it’s just about time and relationship.” When people feel they can count on an organization, they are more likely to take an action endorsed by it. Pastor Smith reinforced this idea, “If you have a relationship and a rapport and trust the person you coordinate with…you will then trust the leader of that organization or government representative who advocates on behalf of the parishioner or advocates on behalf of the community.”

Leveraging government resources to support and invest in the community and faith-based groups makes sense from an efficiency standpoint.

Partnering with organizations that already have a broad reach and high levels of community trust builds trust by association. “You know, there are people who show up every now and then,” McIntosh explained. “They might look in, and the next time they might grab a brochure, then the next time, they might ask a question. And that fourth time is when they say, ‘Okay, I’m going to do this.’ So it’s just about time and relationship.” When people feel they can count on an organization, they are more likely to take an action endorsed by it. Pastor Smith reinforced this idea, “If you have a relationship and a rapport and trust the person you coordinate with…you will then trust the leader of that organization or government representative who advocates on behalf of the parishioner or advocates on behalf of the community.”

Beyond COVID, Hawkins and McIntosh are focused on connecting organizations to government resources and to one another to increase their collective potential impacts. Aggregating the grant-seeking efforts of various organizations is a way of replacing competition for resources with resource-sharing. “There are different pockets of town that need these resources,” says Hawkins, “ And when you are a collective, you have the opportunity to spread those resources even wider.” Harris County is so large that many different organizations work in silos. Hawkins advocates for greater collaboration between organizations of all sizes. She explains, “When you come together and have a complete conversation, it’s an opportunity to help people across the board, those that need the most—those vulnerable populations that don’t always get heard.” Cultivating partnerships between government and community organizations is an elegant way to overcome obstacles facing both entities.

The existing social capital and infrastructure provided by faith-based and community organizations form a conduit to difficult-to-reach populations. And while access to government resources may amplify the efforts of local organizations, increasing the capacity of government institutions makes them more effective. Staci Lofton points out the benefit of having a FUSE Fellow on her team, “Jometra was instrumental in sharing and broadly promoting our best practices, as well as sharing best practices across other jurisdictions with our department.”

The existing social capital and infrastructure provided by faith-based and community organizations form a conduit to difficult-to-reach populations. And while access to government resources may amplify the efforts of local organizations, increasing the capacity of government institutions makes them more effective. Staci Lofton points out the benefit of having a FUSE Fellow on her team, “Jometra was instrumental in sharing and broadly promoting our best practices, as well as sharing best practices across other jurisdictions with our department.”

But building long-term synergies between the county and the community requires systemic support and long-term commitment. Speaking to the larger vision for her FUSE fellowship, McIntosh sums it up, “What I would like to see is a place at the county level, where equity— specifically health equity—can live and thrive and be welcomed. For continuity and sustainability, it has to go beyond just one person doing a fellowship, to how the county works and how the county approaches health services overall.”

Hawkins, referring to a recent program that distributed over 30,000 COVID testing kits in Harris County, agrees that partnership with community organizations is critically important. “We are continuing to listen to the community and what they need. I want to create more sustainable programs like that, where we listen to the community, making sure that we are providing resources they actually need and being equitable about the distribution.” Pastor Smith concurred, “It is a great model for how the government can work when a lot of people don’t believe in the government. Having a middle person advocating makes the difference.”

But building long-term synergies between the county and the community requires systemic support and long-term commitment. Speaking to the larger vision for her FUSE fellowship, McIntosh sums it up, “What I would like to see is a place at the county level, where equity— specifically health equity—can live and thrive and be welcomed. For continuity and sustainability, it has to go beyond just one person doing a fellowship, to how the county works and how the county approaches health services overall.”

Hawkins, referring to a recent program that distributed over 30,000 COVID testing kits in Harris County, agrees that partnership with community organizations is critically important. “We are continuing to listen to the community and what they need. I want to create more sustainable programs like that, where we listen to the community, making sure that we are providing resources they actually need and being equitable about the distribution.” Pastor Smith concurred, “It is a great model for how the government can work when a lot of people don’t believe in the government. Having a middle person advocating makes the difference.”