This FUSE-produced story was originally published on Next City.

On any given day in St. Louis, the jails house more than 1,000 inmates, many of whom are unable to afford the cash bail that would allow them to be released until their trial date. Black residents are detained three times as often as white residents before trial.

St. Louis is not the only city with these stark statistics. A movement has been underway nationwide calling out discrepancies in pretrial detention processes across race and income lines. According to a report from the Prison Policy Initiative that broadly examines mass incarceration in the U.S., more than 540,000 people are detained annually who have not been convicted or sentenced.

In St. Louis, FUSE executive fellow Wilford Pinkney, a former detective for the New York City Police Department, is working with city officials to help establish processes for pretrial reform and, as part of this work, develop procedural alternatives that judges can use in lieu of bail. Pinkney is working under the supervision of Judge Jimmie Edwards, St. Louis’ director of public safety.

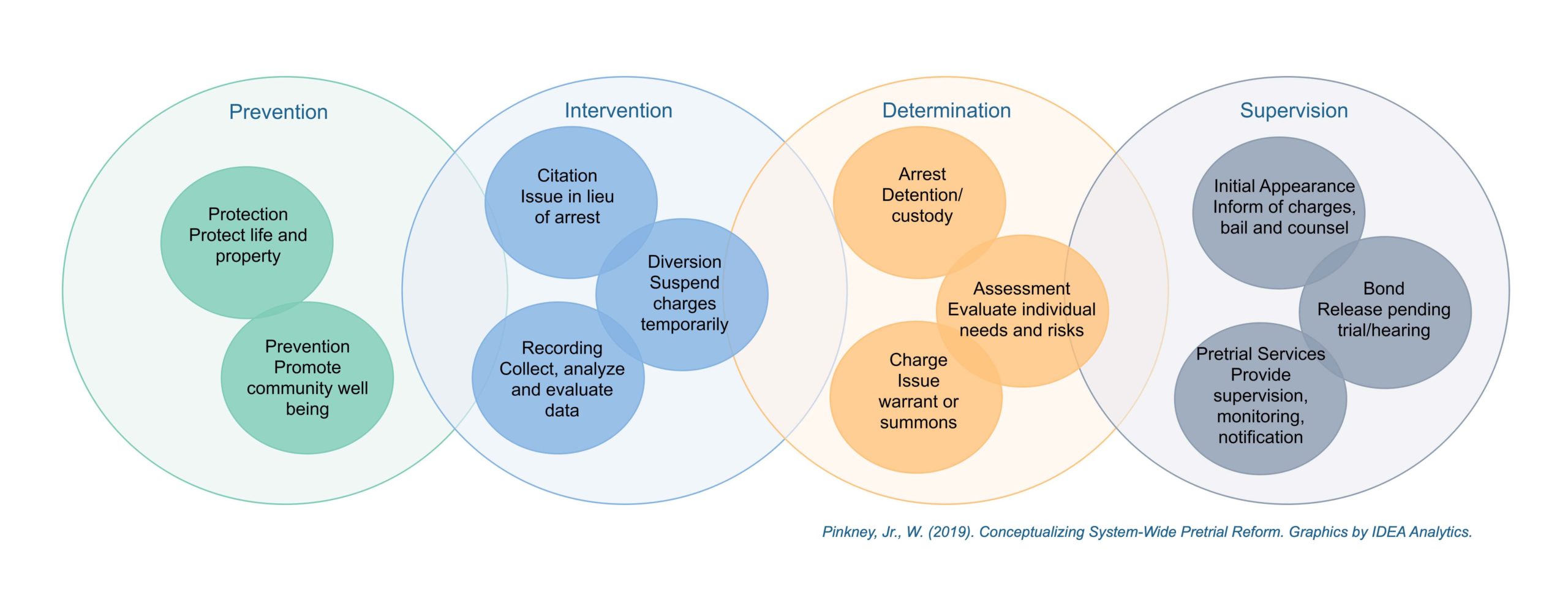

True reform, Pinkney notes, must begin far earlier than when the initial bond is set. Reform should happen in the early stages of the criminal justice process and account for all the interactions that lead up to bond determination. Pinkney believes a holistic re-examination of the system can help point to where interventions can occur — in some cases, before a crime is ever committed — and move the needle toward greater fairness in criminal justice. “The ultimate goal,” Pinkney said, “is to decrease the jail population.”

Understanding the needs of people who are charged, and referring them to services while awaiting trial, could improve outcomes for them and public safety for the city, he notes. For example, healthcare and social-service systems should be overlaid with the pretrial process. “Does it make sense to just release people without addressing needs that may result in them getting arrested again?” he said. “We have to evaluate each person in and of themselves and use whatever set of facts we have about who they are. That’s the thinking that has to change. If we can do this, we will have a better system, fairer outcomes, and less incarceration.”

To break down silos among departments, Pinkney is bringing together key stakeholders — judges, police, probation officers, defense attorneys, and social workers — to tackle this challenge at a systemic level. He aims to build trust, stronger communication, and better collaboration among these stakeholders, all of whom too often work in isolation.

Another tactic to spur communication is assembling a judges panel to discuss pretrial release systems and evidence based practices, such as risk assessment tools and court reminder systems. The panel, to be led by judges who have worked on pretrial reform across the country, will give St. Louis judges the opportunity to hear firsthand the experiences of their peers in other jurisdictions who have implemented or worked with similar pretrial systems.

Pinkney has also been evaluating pretrial systems in cities with comparable populations to St. Louis, including New Orleans and Lexington, Kentucky. Additionally, he has looked at Harris County and El Paso, Texas, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and Springfield, Illinois, as possible models for reform. “One thing I learned is that every place has different needs, politics, and resources,” he said, “so you have to do a gap analysis, assess the systems in place, assess the resources, and then figure out what’s best for your city and county.”

Viable Alternatives

As part of his broader work in pretrial reform, Pinkney has been examining alternatives to bail. A few months ago, Missouri’s highest court ordered new rules that require judges to first consider non-monetary conditions for pretrial release. Other states have already taken similar steps. Last summer, California became the first state to approve legislation to eliminate its cash bail system, and, in 2017, New Jersey enacted legislation that dramatically reduces cash bail.

“Bail reform is not the same as being soft on crime,” said Judge Edwards, a long-time member of the judiciary who has served as an administrative judge of the city’s family court and as chief juvenile court judge. “It’s about due process and fairness, about equitable treatment for all of our citizens irrespective of their station in life.”

When people cannot raise the money for bail, they remain locked up until their case is adjudicated, a process that can take days, weeks, or months. As a result, many lose their jobs, their homes, and custody of their children. Others enter into plea deals because they are desperate to be released. “That’s where we are depriving people of their liberties for no other reason except that they are poor,” Edwards said.

One of the most common alternatives to current bail setting practices is using risk assessment tools, which rely upon algorithms to derive a “score” for a person’s likelihood of showing up for court and committing an offense while released. The score is typically based on such factors as prior arrests and convictions, type of charges, and employment history. Race typically is not a factor. Nonetheless, critics are raising a red flag: More than 100 organizations across the country have called for an end to using these tools, warning that data used to create the scores might be influenced by systemic bias. For example, a person’s record, including prior convictions, could have been affected by racial bias.

Pinkney acknowledges that St. Louis needs to be mindful of this possibility, although he believes risk assessment tools have the potential to work. He also emphasizes that the tool itself is just one piece of a more comprehensive system of information gathering, improved communications, and better service delivery. As such, he wants to organize a stronger matrix of pretrial services for those in need, including substance abuse treatment, mental health counseling, access to housing, education, and job training.

Small Change, Big Payoff

One pilot that Pinkney plans to launch is an automatic notification system — including texts, emails, and phone calls — to remind defendants about court dates. Such a system has reportedly proven to be effective in a number of states, including New York and California. “People often think, when you start talking about failure to appear in court, that people don’t show up because they don’t feel like it — they’re snubbing their nose at the system. Oftentimes, that’s not the case. They may have no way to get there, or they may actually forget because they have a lot of other stuff going on,” said Pinkney.

The cost of these services is pennies per transaction, he adds. “Not showing up costs the courts money in terms of lost time and cases moving more slowly,” Pinkney said. “And, in most places, it costs between $78 and $98 a day to incarcerate someone, which can happen if a person misses their court date — as opposed to one cent to remind them of the date. A small thing like that can make a big difference.”

Pinkney considers one of his biggest challenges to pretrial reform to be that of persuasion: He wants to convince stakeholders not to be constrained by the current system. “If you think about the walls and barriers and restraints as they currently exist, you’re going to limit your ability to think about what should or could happen,” he said. “I want stakeholders to consider what they want a system to be, rather than assuming it has to stay the way it is. That can be a challenge for people. But they have to dare to dream.”

Johanna Wald is a freelance writer and researcher based in Boston. She has written for Education Week, The Crime Report, The Marshall Project, and USA Today.

[Photo credit: Brittney Butler]