Original story published in NextCity.

The night of March 3, 2020, Nashville may never forget. At least 10 tornadoes touched down in parts of Tennessee late in the evening and early into the morning, covering about 175 miles and taking 25 lives in Middle Tennessee, according to local news station Fox 17.

While tornadoes are common in Tennessee, 10 at a time certainly are not. A year prior, EcoWatch reported that states affected most by tornadoes, an area called Tornado Alley, is moving eastward as climate change worsens. In 2020, the environmental outlet suggested the climate crisis could have worsened the storm that year. According to the Tennessean, tornado damage closed more than 20 salons and barbershops along the community’s cornerstone Jefferson Street, a searing loss because African American barbers and hairstylists on the street are important cultural and economic fixtures in their neighborhood. It demolished the second story of a co-working space focused on helping to grow businesses led by people of color. A 2020 Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) report also makes it clear that communities of color haven’t gotten enough disaster mitigation planning and investment.

“Many FEMA programs do not consider the principle of equity,” the report stated. “Damage assessments are based on property ownership, which… disadvantages renters and the homeless population. By perpetually assisting larger communities that already have considerable resources, the smaller, less resource-rich, less-affluent communities cannot access funding to appropriately prepare for a disaster.”

Unfortunately, the tornado wasn’t the last disaster Music City would face that year. Two weeks later, COVID-19 shut down the city, and the CDC reports that white individuals had better access to resources and were less likely to die from the disease. In May, a derecho with winds of 80 miles per hour knocked out power for tens of thousands, and Channel 5 News reported that 128 people died while experiencing homelessness that year. Civil unrest resulted in a fire at the Metro Courthouse, and an extremist bombed a historic downtown area on Christmas Day. The city desperately needed an equitable disaster relief framework to help every Nashvillian recover and prepare for the future.

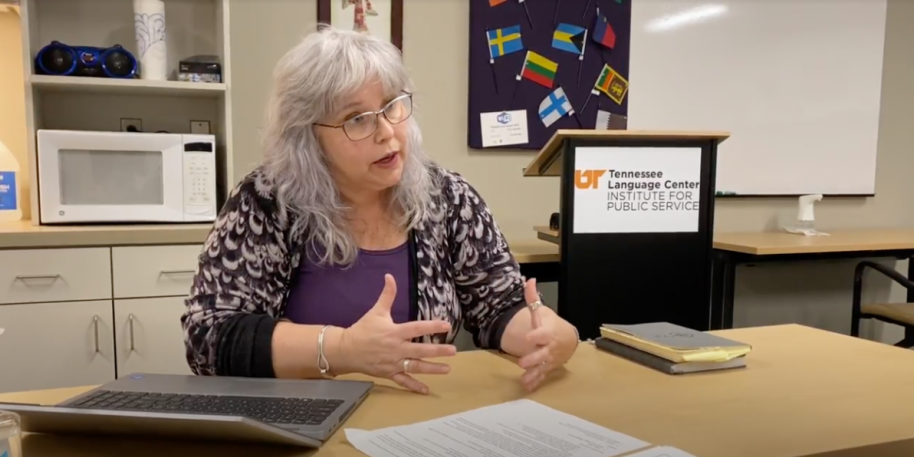

Enter: FUSE, an organization that partners with local governments to design projects that address their toughest challenges. Nashville brought in FUSE to design and scope a project centered around equitable disaster mitigation and conducted a nationwide search for the right talent to lead the effort. Karin Weaver was a natural choice. A Nashville native and nonprofit veteran, Weaver started at the volunteer organization Hands on Nashville just days before the tornado hit and strategized volunteer efforts throughout the recovery process.

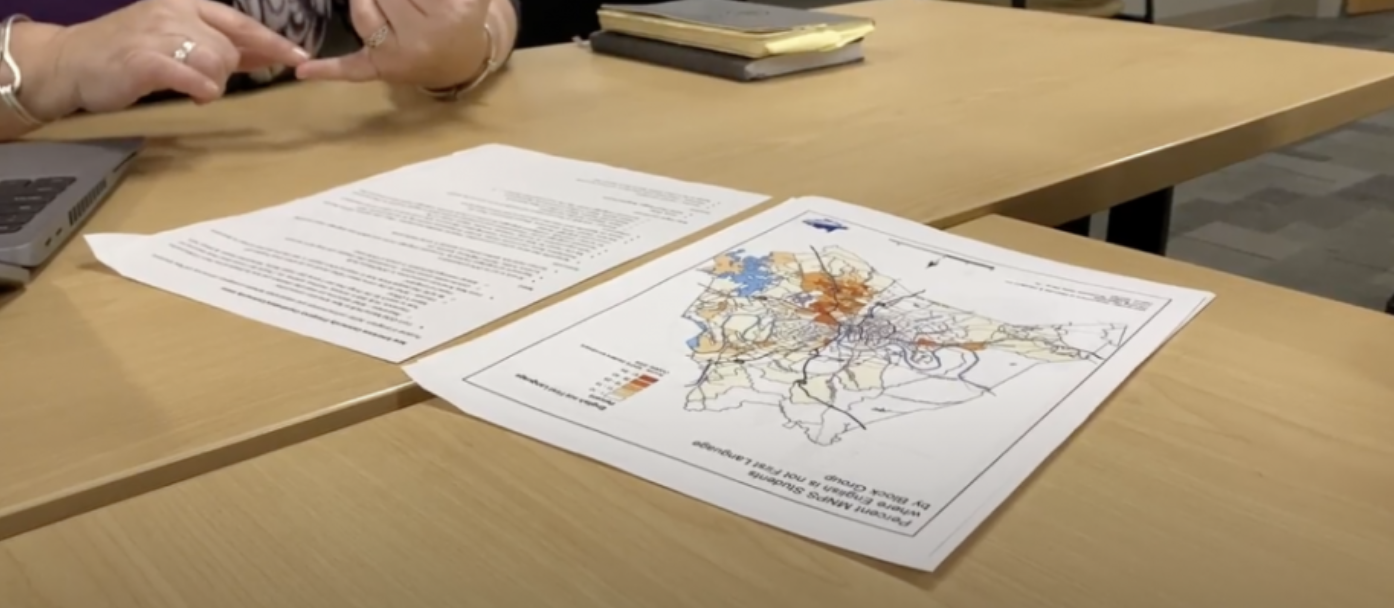

Weaver’s three decades of experience is a boon to the city and the mayor’s office. She joined them through FUSE in October of 2021, and her year-long fellowship is helping Nashville ensure that its long-term resiliency and recovery framework is inclusive and equitable. To do that, Weaver is reviewing multiple city policies to help improve response time and effectiveness, according to Kristin Wilson, chief of operations and performance for Nashville’s Metro government. One critical project she’s tackling involves looking at past programs to develop better ways to help seniors who can’t drive themselves when they’re notified of a need to evacuate. Weaver’s work is also inspiring completely new initiatives to ensure the safety of Nashvillians who don’t speak English.

“The ultimate goal of the partnership is to make sure that Nashville’s disaster response and recovery plan meets the needs of especially vulnerable populations and is sustainable beyond the FUSE Fellow’s tenure,” Weaver says.

The last two years have taken a toll on Nashville’s morale, and Weaver says many still haven’t been able to move forward.

“It’s not in the past yet,” Weaver said just before the second anniversary of the tornado.

That’s why what FUSE Corps does — allowing local governments to address pressing challenges even if they don’t have the capacity themselves — is so essential. Wilson says Weaver’s contributions are priceless.

“Mayor John Cooper is always seeking opportunities for Metro Government to more effectively serve our residents,” Wilson says. “We want to design better systems and infrastructure for future disasters more equitably so that everyone can be well-prepared, get the help they need, and be able to recover as quickly and fully as possible.”

FUSE Executive Fellowships last one year, but departments will often extend fellows’ programs. Local governments that reach out to FUSE frequently name the same pain point that’s holding them back from solving an issue or trying out a new, needed initiative: bandwidth. FUSE partners with local governments and communities to co-design projects that accelerate policies and programs that advance racial equity. They identify and vet experienced professionals to pair the city with the right fellow. So far, FUSE Executive Fellows have worked on over 250 projects in 42 cities and counties across 18 states, serving a combined population of 25 million people.

For Nashville, the experience has been invaluable. Wilson says the city will continue to build on the groundwork Weaver made even after her time with the city is over.

In the wake of the 2020 tornado, many residents took to social media with the hashtag #NashvilleStrong. It’s even painted in murals and artworks around the city. While the mantra doesn’t mean residents will never face hardship, it does reflect the hard work Nashville is putting into making sure every resident is equally safe and cared for.